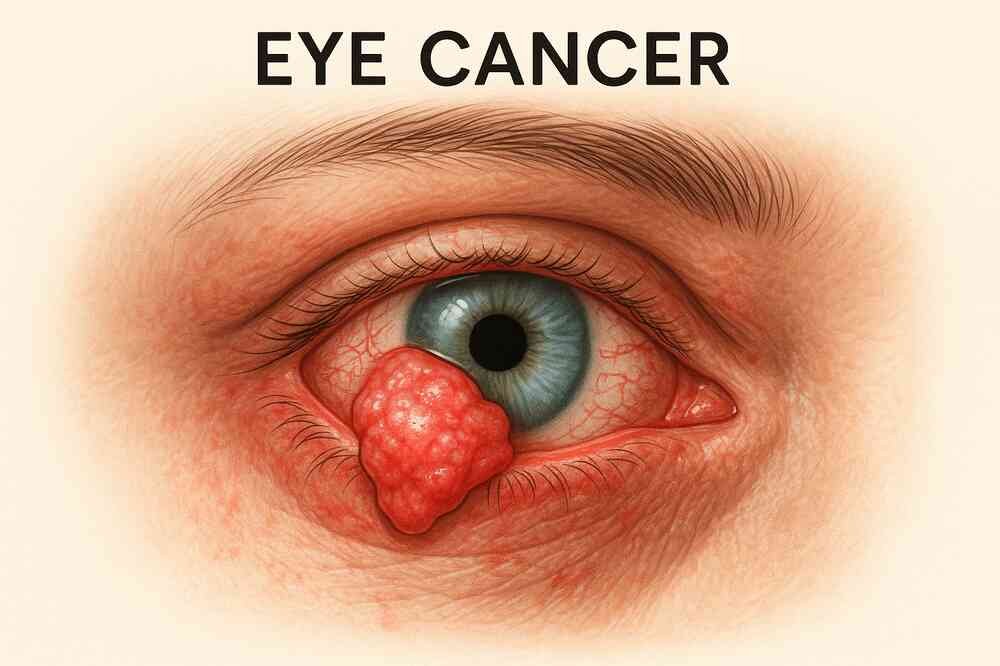

What is an Eye Cancer?

Eye cancer starts in cells in or around the eye. A cancerous (malignant) tumor is a collection of cancer cells that can invade and destroy the tissues around it. It can also spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body.

The eye is the organ that allows you to see. The main part of the eye is the eyeball. It consists of the iris (thin, muscular, colored part of the eye) and the pupil (small black area in the center of the eye). The eyeball is housed in the orbital cavity, or orbit, which protects it. The orbit is a bowl-like cavity made up of skull bones that contains the eyeball, muscles, a lacrimal gland, nerves, fat, and connective tissue. The parts that surround the eyeball are called ancillary, or adnexal structures, and include the eyelid, the conjunctiva (a transparent lining that covers the inner surface of the eyelid and the outer surface of the eyeball), and the lacrimal gland.

Sometimes cells in the eye go through changes that make them grow or behave abnormally. These changes can cause non-cancerous (benign) tumors to form in the eye, such as choroidal hemangioma and eye moles.

Changes to the cells of the eye can also cause precancerous conditions. This means that the abnormal cells are not yet cancerous, but they are likely to become cancer if left untreated. The most common precancerous conditions of the eye are primary acquired conjunctival melanosis and ocular melanosis (high number of cells that produce pigment and excess pigment in and around the eyes).

In some cases, changes in the cells of the eye can cause eye cancer. Most of the time, adult eye cancer starts in melanocytes. These cells make melanin, the pigment responsible for the color of the eyes, skin, body hair and hair. This type of cancer is called melanoma. Ocular melanoma can start in different parts of the eye. But it most often does it inside the eyeball and is called intraocular melanoma.

Lymphoma is another type of cancer that can affect the eye. It is the 2nd most common type of eye cancer.

There are also rare types of eye cancer. These include, among others, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma.

Retinoblastoma is the most common eye cancer in children. It originates in the cells of the retina. Find out more about retinoblastoma.

Other types of cancer can spread to the eye, but this is a different disease from primary eye cancer. Cancer that started in another part of the body and then spreads to the eye is called eye metastasis. The latter is more common than primary eye cancer. It is not usually treated like primary eye cancer. Cancer that spreads to the eye is most often from the breast, lung or digestive tract.

Non-cancerous tumors of the eye

A non-cancerous (benign) tumor of the eye is a lump that does not spread to other parts of the body (not metastasize). The non-cancerous tumor is usually not life threatening.

Different non-cancerous tumors of the eye have many of the same signs and symptoms including a protruding (protruding) eye which is usually painless, redness and altered vision or eye irritation characterized by a burning sensation, itching, swelling. swelling of the eye or the feeling that there is something in our eye, for example.

The following non-cancerous eye tumors are common:

Choroidal hemangioma

Choroidal hemangioma is a slow growing tumor that appears in the blood vessels of the choroid (layer of the wall of the eye). It is the most common type of non-cancerous tumor of the eye in adults.

Most choroidal hemangiomas do not need to be treated immediately. An eye care specialist usually follows up regularly to see if there are any changes. Treatment is started if fluid leaks from the hemangioma into the eye and causes vision problems. Treatment options include laser surgery, photodynamic therapy, and radiation therapy.

Mole

A mole on the eye, like a mole on the skin, is formed when melanocytes (cells that give color to the eyes, skin, hair and body hair) develop in groups. It may appear as an abnormal brown spot on the surface or inside of the eye. The mole, also called a nevus, is most often formed on the choroid, iris or conjunctiva.

Most eye moles do not need to be treated immediately, unless there are signs that they could be cancerous. An optometrist or ophthalmologist usually follows up regularly to see if there are any changes.

Cavernous angioma

Cavernous angioma appears in the blood vessels in the eye socket (orbital cavity) behind the eye. It can make the eye protrude without causing pain (proptosis). Surgery is sometimes used to treat cavernous angioma, but some small tumors do not need to be removed.

Cancerous tumors of the eye

A cancerous tumor in the eye can invade and destroy nearby tissue. Cancerous tumor is also called a malignant tumor. It can also spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body. Most eye cancers have spread there from another area of the body, such as the breast or lung. This is called an eye metastasis. The following information pertains to cancers that start in the eye, that is, primary cancers of the eye.

Melanoma of the eye

Like melanoma of the skin, melanoma of the eye begins in cells called melanocytes. Melanocytes make melanin, which is the substance that gives color to eyes, skin, body hair and hair. Melanoma of the eye can affect the following structures:

eyeball (intraocular melanoma)

conjunctiva (conjunctival melanoma)

eyelid (type of skin melanoma)

orbit, or orbital cavity (orbital melanoma)

Intraocular melanoma

Intraocular melanoma is the most common type of eye cancer in adults and accounts for about 5% of all melanomas. Most intraocular melanomas start in the uvea and are called uveal melanoma. Uveal melanoma is divided into anterior uveal melanoma and posterior uveal melanoma. Anterior uveal melanoma affects the iris in the front (anterior) part of the eye. Posterior uveal melanoma affects structures behind the front part of the eye, either the choroid or the ciliary body. Most uveal melanomas start in the choroid, so you might also hear the term choroidal melanoma.

The most common types of cells in intraocular melanoma are spindle cells and epithelioid cells. Spindle cells are long and flat while epithelioid cells are round. Intraocular melanoma often contains these two types of cells.

Intraocular melanoma is treated differently from melanoma, which affects other parts of the eye, such as the conjunctiva or the eyelid.

Lymphoma of the eye

Lymphoma of the eye, also called ocular lymphoma, is the 2nd most common type of eye cancer. Lymphoma of the eye is usually a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that starts in lymphocytes. Lymphoma of the eye can affect the following structures:

- eyeball (intraocular lymphoma)

- orbit (orbital lymphoma)

- eyelid

- conjunctiva

- lacrimal gland

Retinoblastoma

Retinoblastoma is the eye cancer that affects children the most. Find out more about retinoblastoma.

Rare eye tumors

The following cancerous tumors of the eye are rare.

Squamous cell or squamous cell carcinoma of the eye most often starts in the conjunctiva or eyelid. Squamous cell carcinoma of the eye is the most common type of conjunctival cancer. Squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid is a type of skin cancer other than melanoma.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the eye usually starts in the eyelid and is the most common type of eyelid cancer. CBC of the eyelid is also a type of skin cancer other than melanoma.

Sebaceous eyelid carcinoma most commonly appears on the upper eyelid, near the lash line. It is cancer of the sebaceous glands. These glands secrete an oily substance in tears.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is the most common type of cancer of the lacrimal gland. Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a type of adenocarcinoma that starts in glandular cells.

Orbital sarcoma is a type of soft tissue sarcoma that starts in the orbit (orbital cavity). It can appear in the muscles that move the eye and most often affects children.

Retinal Cancer | Choroidal melanoma, Choroidal metastases, Symptoms, Diagnostic, Treatment

Risk factors for eye cancer

A risk factor is something, like a behavior, substance, or condition that increases the risk of developing cancer. Most cancers are caused by many risk factors, but sometimes eye cancer develops in people who do not have any of the risk factors described below.

In general, eye cancer tends to occur more often in Caucasians than in those of other ethnic groups. In Canada, the number of new eye cancer cases diagnosed each year (incidence) begins to increase in your early 30s. Eye cancer usually affects men and women equally, but by the age of 50 it occurs more often in men.

Risk factors are usually ranked from most important to least important. But in most cases, it is impossible to rank them with absolute certainty.

Known risk factors

There is convincing evidence that the following factors increase your risk for eye cancer.

Primary acquired melanosis

Primary acquired melanosis (PAD) is a condition of the conjunctiva of the eye, which is the transparent lining that covers the inner surface of the eyelid and the outer surface of the eyeball. MAP appears as a brown, flat plaque that contains a lot of melanocytes. Melanocytes are the cells that make melanin, the substance that gives color to eyes, skin, body hair and hair.

PAD most commonly affects Caucasians. It increases the risk of conjunctival melanoma, a type of eye cancer.

Ocular melanosis

Ocular melanosis, also called oculocutaneous melanosis or Ota nevus, is a rare eye condition that is present at birth. In people with this disease, the number of melanocytes is high and there is excess melanin in and around their eyes.

Ocular melanosis increases the risk of developing intraocular melanoma, the most common type of eye cancer.

Pale colored skin, eyes, hair and hair

People with fair or pale complexions are more likely to have intraocular melanoma than people with different skin types. People who have blond or red body hair and hair and blue, green or gray eyes are also more likely to have intraocular melanoma. Their risk is higher since people with these characteristics have less melanin. Melanin is the substance that gives color to the skin, eyes, body hair and hair. Experts believe it also helps protect the skin from ultraviolet (UV) rays.

Moles on the skin

A mole is a non-cancerous lump on the skin, which is usually light brown, dark brown, or flesh colored. Usually, moles are not present at birth, but they often start to appear in childhood. People who have moles on their skin are more likely to have intraocular melanoma in the uvea (uveal melanoma). The uvea is the middle layer of the eye wall that forms the outer part of the eyeball.

Atypical moles increase the risk of intraocular melanoma. The appearance of an atypical mole, or dysplastic nevus, differs from that of a normal mole. Many atypical moles are at least 5mm in diameter, which is larger than normal, and has an irregular shape and an undefined border.

Having dysplastic nevus syndrome (FAMMM) also increases your risk for intraocular melanoma. FAMMM, sometimes called familial multiple atypical melanoma, is an inherited disorder that is characterized by a large number of moles on the body.

Artificial tanning

Tanning beds and sunlamps emit ultraviolet (UV) rays which can damage the eyes and increase the risk of intraocular melanoma.

Welding

Welders are more likely than average to develop eye cancer, especially intraocular melanoma. This increased risk is likely attributable to exposure to ultraviolet (UV) rays emitted by welding tools. It could also be caused by exposure to other harmful substances in the workplace.

HIV or AIDS

People who have a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) are at increased risk of the following types of eye cancer:

Lymphoma of the eye

squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva

This increased risk of getting these types of cancer may be because the virus weakens the immune system or affects the body in other ways.

Possible risk factors

The following factors have been linked to eye cancer, but there is not enough evidence to say that they are known risk factors. More research is needed to clarify the role of these factors in the development of eye cancer.

Sun exposure

The sun is the main source of ultraviolet (UV) rays. Sun exposure is a known risk factor for melanoma of the skin. Research has also shown that it is linked to melanoma of the eye (intraocular melanoma) as well as squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva.

Scientists believe that sun exposure could be a risk factor for eye cancer for several reasons. They found that melanoma appears in the areas of the eye that are most exposed to sunlight. They also indicate that the melanoma of the eye and melanoma of the skin share some risk factors, such as having pale skin or eyes. There is also some evidence that people who work outdoors are at higher risk for eye cancer.

Moles on the eye

Like moles on the skin, moles on the eye (ocular nevi) are non-cancerous. However, people who have moles on their eyes may be at greater risk of one day developing ocular melanoma.

Genetic mutations

Certain genetic changes, or mutations, have been linked to an increased risk of eye cancer. Researchers continue to study genes to find which ones may play a role in the development of eye cancer.

BAP1 gene mutation

The BAP1 gene (BRCA1 associated protein-1) helps control cell growth and may limit the growth of cancer cells. This is called a tumor suppressor gene. A mutation in the BAP1 gene can increase the risk of uveal melanoma but also of mesothelioma and melanoma of the skin. Health care professionals sometimes tell people with a mutation in the BAP1 gene that they have BAP1 syndrome.

Mutation of the GNA11 gene

The GNA11 gene makes a protein that helps control cell growth and the normal process of programmed cell death (apoptosis). This gene is found in certain types of cells, including those of the eyes, skin, heart and brain. A mutation in the GNA11 gene can increase the risk of uveal melanoma.

Family history of intraocular melanoma

In some families, there are more cases of intraocular melanoma than you might expect. When there is a family history of intraocular melanoma, it is because one or more close blood relatives have been diagnosed with the disease. Sometimes it is not clear whether this family disposition is due to chance, to a lifestyle that family members have in common, to a hereditary factor (such as having a mutation in the BAP1 gene) or to an association. of these elements.

BAP1 syndrome is an inherited syndrome that has been linked to an increased risk of uveal melanoma, a type of intraocular melanoma.

Professional exposure

People who work in the chemical industry, including chemists, chemical engineers and chemical technicians, or in the culinary industry may be at increased risk of developing eye cancer. More research is needed to understand how working in these industries increases this risk.

Freckles

The presence of freckles, especially in children, can increase the risk of eye cancer. This link between freckles and eye cancer may be due to exposure to UV rays from the sun, which contributes to the development of freckles.

Unknown risk factors

It is not yet clear whether the following factors are linked to eye cancer. This may be because researchers are unable to definitively establish this link, or the studies have yielded different results. More research is needed to find out if the following are risk factors for eye cancer:

- personal history of skin melanoma

- family history of breast or ovarian cancer (risk of eye cancer may be linked to a mutation in the BRCA2 gene)

- taking medicines that weaken the immune system (immunosuppressants)

- human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, which could be linked to squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva

- infection with Chlamydophila psittaci (C. psittaci), which may be related to intraocular lymphoma

Diagnosis of eye cancer

Diagnosis is a process of identifying the cause of a health problem. The diagnostic process can seem long and overwhelming. It’s okay to worry, but try to remember that other medical conditions can cause symptoms similar to eye cancer. It is important that the healthcare team rule out any other possible cause of the condition before making a diagnosis of eye cancer. Tests to diagnose eye cancer are usually used when:

- a routine eye exam suggests an eye disorder (most eye cancers are found this way);

- symptoms of this disease are observed.

The following tests are usually used to rule out or diagnose eye cancer. Many tests that can diagnose cancer are also used to determine its stage, that is, how far the disease has progressed. Your doctor may also give you other tests to check your general health and help plan your treatment.

Health history and physical examination

Your health history consists of a checkup of your symptoms, risk factors, and any medical events and conditions you may have had in the past. Your doctor will ask you questions about your personal history:

- symptoms that suggest eye cancer

- certain eye conditions (primary acquired melanosis and ocular melanosis)

- moles on the skin or on the eye

- HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) or AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome)

time spent in the sun and artificial tanning - welding

Your doctor may also ask you questions about your family history of eye cancer and other cancers.

The physical exam allows your doctor to look for any signs of eye cancer. During the physical exam, your doctor may:

- observe the surface of your eye;

- feel your neck and abdomen for signs of swelling.

Eye examination

The eye exam is performed by an eye care specialist. The optometrist is the specialist you likely see for a routine eye and vision test. If there is a problem, your doctor or optometrist may refer you to an ophthalmologist, which is a doctor who specializes in eye disorders. An eye exam is done to check:

- your vision;

- the movement of your eyes;

- the presence of abnormal areas on the surface or inside of your eyes.

The eyes are examined using various instruments such as:

- ophthalmoscope – an instrument with a light and a magnifying lens that examines the back of the eye, including the retina and optic nerve

- slit lamp – a type of microscope that uses an intense beam of light to examine the inside of the eye

- gonioscope – special lens applied directly to the surface of the eye to examine the front of the eye

- transillumination – using a special light instrument placed on the eyelid to examine the front of the eye

- Optomap device (retinal imaging) – device for examining the retina using a digital imaging system that produces images of almost the entire retina

- optical coherence tomography (OCT) – a type of imaging test that uses light waves to produce cross-sectional images of the retina, choroid, and sclera tonometry – a test that measures the pressure inside the eye by applying an instrument to the cornea or blowing hot air on the surface of the eye

Before the test, your doctor may put eye drops in your eyes to make your pupils larger (dilate). This helps him to see the structures inside the eye better. Since these drops can affect your eyesight for a few hours, you shouldn’t drive after the appointment.

Ultrasound

In an ultrasound, high-frequency sound waves are used to produce images of parts of the body. She allows to :

- diagnose ocular melanoma;

- determine the location and size of the tumor in the eye;

- find out if the cancer has spread to nearby parts of the body;

- find out if the cancer has spread to the liver;

- plan radiotherapy;

- check how well the treatment is working.

An ultrasound scan of the eye uses a small wand-like instrument called an ultrasound probe. It is gently applied to closed eyelids or directly to the surface of the eye. Sometimes anesthetic drops are put in the eye to numb it before the ultrasound is done.

Ultrasonic biomicroscopy is sometimes used rather than routine ultrasound. This technique provides an image more detailed structure present on the front of the eye.

In abdominal ultrasound, a larger ultrasound probe is used to look at the abdomen. Sometimes an abdominal ultrasound is done to see if the cancer has spread to the liver.

Angiography

An angiogram is an x-ray that takes pictures of the blood vessels. An orange or green dye is injected into the arm. It travels through the blood vessels inside the eye. Drops are first put in the eye to enlarge (dilate) the pupil.

Complete blood count

The complete blood count is used to assess the quantity and quality of white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets. The blood count is used to check your general health.

Liver and kidney function tests

Liver and kidney function tests measure the level of chemicals in the blood. These tests can show how well the liver and kidneys are functioning and help find something abnormal in these organs. If the result of a liver function test is abnormal, it may indicate that eye cancer has spread to the liver.

Biopsy

During a biopsy, the doctor removes tissue or cells from the body for analysis in the laboratory. The pathologist’s report confirms whether or not there are cancer cells in the sample. The eye biopsy removes part of the suspicious area (incisional biopsy) or the entire suspicious area (excisional biopsy).

Most types of cancer require a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. But some eye cancers only require an eye exam or imaging test. Doctors try to avoid removing tissue from the eye since it can be difficult to collect the tumor without damaging the eye or spreading the cancer.

An eye biopsy is most often done:

- when you are unable to make a diagnosis after receiving the results of other tests;

- when the doctor recommends cytogenetic tests;

- to remove a suspicious area around the eye, such as the eyelid.

There are special types of biopsies that help diagnose eye cancer or see where it has spread.

Fine needle biopsy

A fine needle biopsy can be done to diagnose eye cancer, especially when the results of other tests are not clear. A very fine needle is used to remove a few cells from the abnormal area of the eye.

Vitreous biopsy

A vitreous biopsy, also called a vitrectomy, is a procedure that helps diagnose lymphoma in the eye. Very small instruments are used to remove some of the gelatinous fluid inside the eye (vitreous body) through several small incisions made in the eye.

Bone marrow puncture and biopsy

Bone marrow puncture and biopsy are procedures that remove cells from the bone marrow for examination under a microscope. It is used if a person has been diagnosed with lymphoma of the eye. This can tell if the lymphoma has spread to the bone marrow.

Genetic tests

Genetic tests are used to look for changes in genes, chromosomes or proteins that are sometimes seen in people with cancer. The results of genetic tests can help doctors make a prognosis and plan treatment. Genetic tests can be done on a sample of cells taken during a biopsy or tissue removed during surgery.

Cytogenetic tests

Cytogenetics is the study of a cell’s chromosomes, including their number, size, shape and arrangement. Cytogenetic tests (analysis of chromosomes) reveal changes in chromosomes. It helps doctors predict the prognosis for people with eye cancer. The results of cytogenetic tests also help doctors plan treatment and predict the likelihood of the cancer coming back or spreading.

Gene expression profile

The gene expression profile allows doctors to look at many genes at once so they can know which are active and which are not. Genetic expression can help determine which eye cancers are most likely to spread.

Computed tomography (CT)

During a CT scan (CT), special x-ray machines are used to produce 3-dimensional and cross-sectional images of the body’s organs, tissues, bones and blood vessels. A computer assembles the photos into detailed images.

You can do a CT scan for:

- know the size of the tumor in the eye;

- find out if the eye cancer has spread to parts of the body near the tumor

- find out if the eye cancer has spread to areas far from the tumor.

A dye (contrast medium) may be given by mouth or by injection into a vein (intravenously), or both, before the CT scan. The dye can help the doctor see certain areas of the body better. If you’ve ever had an allergic reaction to a dye, tell your doctor or a member of the radiology department.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses powerful magnetic forces and radio waves to produce cross-sectional images of the body’s organs, tissues, bones, and blood vessels. A computer assembles the images into 3-dimensional snapshots.

You can do an MRI for:

- know the size of the tumor in the eye;

- find out if the eye cancer has spread to parts of the body near the tumor

- find out if eye cancer has spread to areas far from the tumor, including the brain and spinal cord.

A dye or colouring agent (Gadolinium contrast medi may be injected into a vein (intravenously) before the MRI. The dye can help the doctor see certain areas of the body better. If you’ve ever had an allergic reaction to a dye, tell your doctor or a member of the radiology department.

Pulmonary radiography

In an x-ray, low-dose radiation is used to produce images of the body’s structures on film. It is sometimes used to find out if eye cancer has spread to the lungs.

Find out more about x-rays.

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

A positron emission tomography (PET) scan uses a radioactive material called a radiopharmaceutical to detect changes in the metabolic activity of body tissues. A computer analyzes patterns of radioactivity distribution and produces 3-dimensional, color images of the region under examination. A PET scan is sometimes used to see if the eye cancer has spread to areas far from the tumor.

PET / CT

PET / CT combines computed tomography with positron emission tomography. It is sometimes used to find out if eye cancer has spread to the lymph nodes or other areas of the body.

Histological classification of eye cancer (grade)

The grade is defined by the appearance of cancer cells compared to normal cells. To determine the grade of eye cancer, the pathologist examines a sample of tissue taken from the tumor in the eye under a microscope. The pathologist assigns cancer a grade of 1 to 3 or 0 to 4 depending on the type of eye cancer. The lower this number, the lower the rank.

Your doctor does not need to know the grade of eye cancer to plan your treatment. They may plan your treatment based on the results of other tests such as eye exams and imaging tests. The cancer is not graded unless you have had a biopsy or surgery to remove tissue in your eye.

Knowing the grade gives your healthcare team an idea of how quickly cancer can grow and how likely it is to spread. It helps him plan your treatment. The grade can also help the healthcare team determine the possible outcome of the disease (prognosis) and predict how the cancer might respond to treatment.

Histological classification of intraocular melanoma

The grade is the description of the type of cells seen in the tumor. Intraocular melanoma is made up of spindle cells, epithelioid cells, or a mixture of these two types of cells.

Low-grade intraocular melanoma is made up mostly of spindle cells. This cancer tends to grow slowly and is less likely to spread. High-grade intraocular melanoma is made up mostly of epithelioid cells. This cancer tends to grow faster and is more likely to spread than low grade cancer.

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | spindle cell melanoma (more than 90% spindle cells) |

| 2 | mixed cell melanoma (more than 10% epithelioid cells and less than 90% spindle cells) |

| 3 | epithelioid melanoma (more than 90% epithelioid cells) |

Stages of eye cancer

Staging describes or classifies a cancer based on how much cancer there is in the body and where it is when first diagnosed. This is often called the extent of cancer. Information from tests is used to find out the size of the tumour, which parts of the organ have cancer, whether the cancer has spread from where it first started and where the cancer has spread. Your healthcare team uses the stage to plan treatment and estimate the outcome (your prognosis).

The most common staging system for eye cancer is the TNM system. For eye cancer there are 4 stages. Often the stages 1 to 4 are written as the Roman numerals I, II, III and IV. Generally, the higher the stage number, the larger the cancer is or the more the cancer has spread. Talk to your doctor if you have questions about staging.

When describing the stage, doctors may use the words intraocular, extraocular, regional or distant. Intraocular means that the cancer is only inside the eye. Extraocular means that the cancer has grown outside of the eye. Regional means close to or around the eye. Distant means in a part of the body farther from the eye.

Find out more about staging cancer:

Stages of intraocular melanoma of the iris

Stage of intraocular melanoma of the iris is based on the size of the tumour, where the tumour is in the eye and if it has spread outside of the eye.

Stage 1

The tumour is only in the iris and is not more than 1/4 the size of the iris.

Stage 2A

The tumour is any of the following:

It is only in the iris and is more than 1/4 the size of the iris.

It is only in the iris and is causing glaucoma.

It has grown next to or into the ciliary body without causing glaucoma.

Stage 2B

The tumour has grown next to or into the choroid without causing glaucoma.

Or

The tumour has grown next to or into the ciliary body, choroid or both. The tumour has also grown into the sclera.

Stage 3A

The tumour has grown next to or into the ciliary body, choroid or both and is causing glaucoma.

Or

The tumour has grown outside of the sclera and this part of the tumour is not larger than 5 mm in diameter.

Stage 3B

The tumour has grown outside of the sclera and this part of the tumour is more than 5 mm in diameter.

Stage 4

The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes or the cancer has spread to other parts of the body (called distant metastasis), such as to the lungs, liver or bone. Cancer that has spread to a distant part of the body is also called metastatic eye cancer.

Stages of intraocular melanoma of the ciliary body and choroid

Stage of intraocular melanoma of the ciliary body and choroid is based on the size of the tumour, where the tumour is in the eye and if it has grown outside of the eye or spread to other parts of the body.

Size category

A size category is given from 1 to 4 for melanoma of the ciliary body and choroid. The size category is based on the thickness (height) and largest diameter at the base of the tumour. Category 1 tumours are the smallest and category 4 tumours are the largest.

Category 1

The tumour is either:

not more than 12 mm wide and not more than 3 mm thick

not more than 9 mm wide and 3.1 to 6 mm thick

Category 2

The tumour is any of the following:

12.1 to 18 mm wide and not more than 3 mm thick

9.1 to 15 mm wide and 3.1 to 6 mm thick

not more than 12 mm wide and 6.1 to 9 mm thick

Category 3

The tumour is one of the following:

15.1 to 18 mm wide and 3.1 to 6 mm thick

12.1 to 18 mm wide and 6.1 to 9 mm thick

3.1 to 18 mm wide and 9.1 to 12 mm thick

9.1 to 15 mm wide and 12.1 to 15 mm thick

Category 4

The tumour is one of the following:

more than 18 mm wide and may be any thickness

15.1 to 18 mm wide and 12.1 to 15 mm thick

12.1 to 18 mm wide and more than 15 mm thick

Stage 1

The tumour is size category 1 and only in the choroid.

Stage 2A

The tumour is size category 1 and one of the following:

The tumour has grown into the ciliary body.

The tumour has grown outside the eyeball, and this part of the tumour is not more than 5 mm thick.

The tumour has grown into the ciliary body and outside of the eyeball. The part of the tumour outside of the eyeball is not more than 5 mm thick.

The tumour is size category 2 and is only in the choroid.

Stage 2B

The tumour is size category 2 and has grown into the ciliary body.

Or

The tumour is size category 3 and only in the choroid.

Stage 3A

The tumour is one of the following:

It is size category 2 and has grown outside of the eyeball. The part of the tumour outside of the eyeball is not more than 5 mm thick.

It is size category 2 and has grown into the ciliary body. The tumour has also grown outside of the eyeball, and this part of the tumour is not more than 5 mm thick.

It is size category 3 and has grown into the ciliary body.

It is size category 3. It has grown outside of the eyeball, and this part of the tumour is not more than 5 mm thick.

It is size category 4 and only in the choroid.

Stage 3B

The tumour is one of the following:

It is size category 3 and has grown into the ciliary body. The tumour has also grown outside of the eyeball, and this part of the tumour is not more than 5 mm thick.

It is size category 4 and has grown into the ciliary body.

It is size category 4. It has grown outside of the eyeball, and this part of the tumour is not more than 5 mm thick.

Stage 3C

The tumour is size category 4 and has grown into the ciliary body. It has also grown outside of the eyeball, and this part of the tumour is not more than 5 mm thick.

Or

The tumour has grown outside of the eyeball, and this part of the tumour is more than 5 mm thick.

Stage 4

The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes or to other parts of the body (called distant metastasis), such as to the lungs, liver or bone. Cancer that has spread to a distant part of the body is also called metastatic eye cancer.

Recurrent eye cancer

Recurrent eye cancer means that the cancer has come back after it has been treated. If it comes back in the same place that the cancer first started, it’s called local recurrence. If it comes back in tissues or lymph nodes close to where it first started, it’s called regional recurrence. It can also recur in another part of the body. This is called distant metastasis or distant recurrence.

If eye cancer spreads

Cancer cells can spread from the eye to other parts of the body. This spread is called metastasis.

Understanding how a type of cancer usually grows and spreads helps your healthcare team plan your treatment and future care. If eye cancer spreads, it can spread to the following:

- optic nerve

- structures in the eye socket (orbit), including the bones of the orbit

- eyelid

- lacrimal gland (a gland that makes tears)

- paranasal sinuses (hollow chambers around the nose)

- parotid gland (a gland that makes saliva)

- skin

- lymph nodes

- liver

- bone

- brain

- lung

Prognosis and survival for eye cancer

If you have eye cancer, you may have questions about your prognosis. A prognosis is the doctor’s best estimate of how cancer will affect someone and how it will respond to treatment. Prognosis and survival depend on many factors. Only a doctor familiar with your medical history, the type, stage and characteristics of your cancer, the treatments chosen and the response to treatment can put all of this information together with survival statistics to arrive at a prognosis.

A prognostic factor is an aspect of the cancer or a characteristic of the person that the doctor will consider when making a prognosis. A predictive factor influences how a cancer will respond to a certain treatment. Prognostic and predictive factors are often discussed together. They both play a part in deciding on a treatment plan and a prognosis.

The following are prognostic factors for eye cancer:

Stage

Stage is an important prognostic factor for eye cancer. A lower stage eye cancer has a better prognosis.

Location of the cancer

The location of the eye cancer helps to predict a prognosis.

Intraocular melanoma

A melanoma of the iris often has a better prognosis than a melanoma of the choroid or ciliary body. This is because melanomas of the iris can be seen from the outside of the eye so they are often found at an early stage when they are small. Melanoma of the ciliary body or choroid is typically diagnosed at a more advanced stage so these tumours have a poorer prognosis. Melanoma that starts to grow in other parts of the eye and spreads (metastasizes) to the ciliary body also has a poorer prognosis.

Lymphoma of the eye

Lymphoma that develops outside of the eyeball (called extraocular lymphoma) generally has a better prognosis than lymphoma that develops inside the eyeball (intraocular lymphoma).

Cancer spread outside of the eye

Cancer that has spread outside of the eye has a less favourable prognosis than cancer that hasn’t spread outside of the eye.

Cell type

Spindle cell intraocular melanoma has a better prognosis than epithelioid cell intraocular melanoma or mixed cell intraocular melanoma (this is a mix of both types of cells). Most melanomas of the iris are the spindle cell type so they tend to have a favourable prognosis.

Mitotic counts

Mitotic count is the number of cells that are in the process of dividing (called mitosis) when seen under a microscope. Tumours that have higher mitotic counts tend to grow more quickly than those with lower mitotic counts. Eye cancer that has a low mitotic count has a better prognosis than an eye cancer with a higher mitotic count.

Tumour size

Generally, a smaller eye tumour has a better prognosis than a larger tumour. Smaller intraocular melanomas have a lower chance of spreading than larger tumours.

People with small to medium-sized intraocular melanoma are also more likely to be able to see with the affected eye after treatment compared to people with larger tumours.

Chromosome changes

If any tissue is removed from the tumour during a biopsy or surgery, genetic tests may be used to look for changes to the chromosomes. Some changes to chromosomes are linked to a higher risk of the cancer spreading and a poorer prognosis. This includes:

a missing chromosome 3 (called monosomy 3)

loss of part of chromosome 6 (6q)

an extra copy of part of chromosome 8 (8q)

People with intraocular melanoma who have lost all or part of one of the copies of chromosome 3 tend to have tumours that are larger, have spread to the ciliary body and have epithelioid cells.

People who have an extra part of chromosome 6, called a 6p gain, tend to have a better prognosis.

Genetic changes

People whose tumours have certain gene mutations or too many copies (called overexpression) of certain genes tend to have a poorer outcome. The following genetic changes are linked to a worse prognosis in people with intraocular melanoma:

too many copies of the DDEF1 gene on chromosome 8

BAP1 mutations

Gene expression profiling to predict risk of cancer spreading

Gene expression profiling is a way for doctors to analyze many genes at the same time to see which are turned on and which are turned off. Doctors have found that gene expression profiling can help predict the risk of cancer spreading in people with uveal melanoma, a type of intraocular melanoma. This test helps to classify the cancer into 2 groups (called classes). Class 1 uveal melanoma has a better prognosis than class 2 uveal melanoma.

Ki-67 tumour marker

A tumour marker is a naturally occurring substance in the body. An abnormal amount of a tumour marker can indicate the presence of cancer or help predict prognosis. Ki-67 is a tumour marker that shows cells that are dividing. People with intraocular melanoma whose tumours have Ki-67 have a risk of the cancer spreading to other parts of the body.

Age

Younger people have a better prognosis than older people.

Treatments for eye cancer

If you have eye cancer, your healthcare team will create a treatment plan just for you. It will be based on your health and specific information about the cancer. When deciding which treatments to offer for eye cancer, your healthcare team will consider:

- the type of eye cancer

- the size and location of the tumour in the eye

- whether or not the cancer has spread outside of the eye

- the effect the treatment will have on your vision

- your age and general health

- your personal preferences

The goal of treating eye cancer is to prevent it from spreading and to save your vision whenever possible. You may be offered one or more of the following treatments for eye cancer.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a common treatment for eye cancer. It may be used as the main treatment or before or after surgery. The types of radiation therapy that are most often used to treat eye cancer are:

- brachytherapy

- external beam radiation therapy

Surgery

Surgery is a common treatment for eye cancer. Depending on the stage and size of the tumour, you may have one of the following types of surgery.

Eye resection is done to remove the tumour and a small amount of healthy tissue around the tumour.

Enucleation is surgery to remove the eyeball and part of the optic nerve. It may be used to remove large tumours in the eye or when other treatments haven’t worked.

Orbital exenteration is surgery that removes the parts inside the eye socket (orbit). This includes the eyeball, eyelid, muscles, nerves and fat.

Mohs micrographic surgery removes the tumour in layers. Each layer is looked at in the lab until no cancer cells are seen. Mohs surgery is sometimes used to treat a tumour in the eyelid or conjunctiva.

Cryosurgery uses extreme cold to freeze and destroy tissue. It is sometimes used to treat a tumour in the conjunctiva or eyelid.

Laser surgery uses a laser beam to destroy abnormal cells. It is sometimes used to treat small tumours in the eye.

Liver resection is sometimes done if eye cancer has spread to the liver. A liver resection removes the tumour and a healthy margin of tissue around the tumour.

Reconstructive surgery is sometimes done to help your eye to move normally and improve how your face looks (your appearance) after surgery to remove a tumour in the eyelid.

Surgery is done to place a brachytherapy plaque in the eye. Brachytherapy for eye cancer uses radioactive seeds attached to a circular piece of metal (called a plaque) to deliver radiation to the eye tumour.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is often used to treat lymphoma of the eye and is sometimes used to treat melanoma of the eye.

Find out more about chemotherapy.

Active surveillance (watchful waiting)

In active surveillance (watchful waiting), the healthcare team watches for signs and symptoms to appear. The doctor will take pictures of the eye to see if the tumour is starting to grow. Active surveillance is sometimes used when there are no signs or symptoms, the tumour is small and doesn’t appear to be growing or there is a low risk of the cancer spreading. It may also be an option for people who are older with other serious medical conditions or who have a tumour in the only useful eye. You will begin treatment if there are signs that the cancer is starting to grow.

Active Cancer Surveillance and Visits | Monitoring and Follow-up for Cancer Survivors

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy uses drugs to target specific molecules (such as proteins) on or inside cancer cells to stop the growth and spread of cancer. It is sometimes used to treat eye cancer. Targeted therapy drugs used to treat eye cancer include:

- rituximab (Rituxan)

- ibritumomab (Zevalin)

- bevacizumab (Avastin)

- ranibizumab (Lucentis)

- imatinib (Gleevec)

- sorafenib (Nexavar)

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses the immune system to help destroy cancer cells. Interferon alfa-2b (Intron A) is an immunotherapy drug that is sometimes used to treat a tumour of the eyelid or lymphoma of the eye.

Find out more about Immunotherapy Cancer Treatment | Types, To receive, Side effects

If you can’t have or don’t want cancer treatment

You may want to consider a type of care to make you feel better without treating the cancer itself. This may be because the cancer treatments don’t work anymore, they’re not likely to improve your condition or they may cause side effects that are hard to cope with. There may also be other reasons why you can’t have or don’t want cancer treatment.

Talk to your healthcare team. They can help you choose care and treatment for advanced cancer.

Follow-up care

Follow-up after treatment is an important part of cancer care. You will need to have regular follow-up visits after treatment has finished. These visits allow your healthcare team to monitor your progress and recovery from treatment.

Clinical trials

A few clinical trials in certain countries are open to people with eye cancer. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, find and treat cancer. Find out more about clinical trials.

Questions to ask about treatment

To make the decisions that are right for you, ask your healthcare team questions about treatment.

Questions to ask about treatment

To make the decisions that are right for you, ask your healthcare team questions about treatment.

The following are questions that you can ask the healthcare team about treatment options. Choose the questions that fit your, or your child’s, situation and add questions of your own. You may find it helpful to take the list to the next appointment and to write down the answers.

Is treatment available for this type of cancer?

What are the treatment options?

Which treatment do you recommend? Why?

Will more than one treatment be given?

What are the benefits and risks of having treatment?

What are the chances that treatment will be successful?

How will we know that the treatment is working?

Who will do the treatment?

When will treatment begin? Is there a waiting list for treatment?

How is the treatment given?

Where will the treatment be given? Does this treatment require a hospital stay?

Can a support person (such as a partner, parent or friend) be present during treatment?

What can I do to prepare for treatment?

How long will the treatment last?

What are the possible side effects of treatment? When would they start? How long do they usually last?

What can be done to help manage side effects?

What else should be considered before we make a decision about treatment?

What might happen without treatment?

How much time can be taken before we make a decision about treatment?

List of all Cancers

The word “cancer” is a generic term for a large group of diseases that can affect any part of the body. We also speak of malignant tumors or neoplasms. One of the hallmarks of cancer is the rapid multiplication of abnormal growing cells, which can invade nearby parts of the body and then migrate to other organs. This is called metastasis, which is the main cause of death from cancer. Types of cancer (in alphabetical order of the area concerned):

Information: Cleverly Smart is not a substitute for a doctor. Always consult a doctor to treat your health condition.

Sources: PinterPandai, American Cancer Society, NHS (UK), American Academy of Ophthalmology

Photo powered by chatGPT