Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP)

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a rare brain disorder that causes problems with movement, walking and balance, and eye movement.

Originally called Steele-Richardson-Olszewski disease, after the three physicians who described it in 1904, PSP has been recognized as a disease in its own right since 1964. It causes progressive paralysis of eye movements. Its most recent diagnostic criteria were established in 2017 by the Movement Disorder Society.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (progressive supranuclear palsy, PSP, and progressive supranuclear palsy, Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome) is a degenerative disease of the brain, especially the basal ganglia. The basal ganglia are areas of the brain that play an important role in controlling automatic movement. Damage to them can cause problems with moving and maintaining balance, with eye control, swallowing control and speech control. PSP is related to Parkinson’s disease, the disease is similar in many symptoms. It is not uncommon for the less common PSP to be mistaken for Parkinson’s disease. PSP is combined with other Parkinson-like diseases under the term atypical Parkinson’s syndrome or Parkinson-plus.

Explanation of the term

Usually a “paralysis” is a motor weakness or paralysis of a part of the body.

The term “supranuclear” refers to the nature of the eye problem in PSP. Although some patients with PSP describe their symptom as “blurry,” the real problem is the inability to target the eyes properly due to weakness (or paralysis) in the muscles that move the eyeballs. These muscles are controlled by nerve cells that reside in clusters, or “nuclei,” near the base of the brain, in the brainstem.

Most of the problems that affect eye movements originate from these nuclei in the brain, but in PSP the problem stems from parts of the brain that control these nuclei themselves. These “higher” control zones are what the prefix “supra” refers to in “supranuclear” (above nuclei).

Symptoms

The first symptoms appear between the ages of 55 and 70 on average.

There are many forms of PSP and the first signs of the disease can vary widely. Some of the most common symptoms include:

- Progressive balance disorders and frequent falls

- Slowing eye movements

- Blurred vision impression

- Dry eyes and sensitivity to light

- Behavior changes: apathy, impulsiveness, aggressiveness, instability of attention …

- Difficulty speaking

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

- Slowness of thought and some memory problems

- Muscle stiffness

- An inability to control eye and eyelid movement, including focusing on specific objects or looking up or down at something

The rate at which the symptoms progress can vary widely from person to person.

However, the clinical signs (symptoms) presented by the patient, associated with neuropsychological tests, brain imaging by MRI and an oculomotor examination strongly guide the clinician towards a diagnosis of PSP.

In the first years of the disease, symptoms may be similar to those of Parkinson’s disease, however more suggestive signs make the diagnosis highly likely. The specific criteria are oculomotor disorders and falls backwards due to postural instability (retropulsions).

Oculomotor symptoms are very often characterized by difficulty moving the eyes up or down, following a moving object with the eyes. The upper eyelids may rise and retract causing a peculiar facies with an expression of amazement or wide-eyed eyes. Muscle contractures are also observed especially in the neck with difficulty in flexing the neck and a posture of the head extended backwards (retrocolis).

The absence or non-permanence of resting tremors also differentiates PSP from Parkinson’s disease.

How to diagnose it?

It is still little known and underdiagnosed, which is why it takes an average of 3 to 4 years between the first symptoms and the diagnosis. The latter is based on the age of the patient, the progression of the disease with a progressive accentuation of the symptoms, the neurological examination and the complementary examinations, which make it possible to exclude other disorders.

The neurological exam studies eye movements, balance, speed and richness of movement, language and intellectual functions.

Biological sampling. While there is currently no biomarker to diagnose PSP, a blood test and in some cases a sample of cerebrospinal fluid is useful in detecting disease that may mimic PSP. Some of these diseases are curable, so the importance of such a toll should not be underestimated!

Brain MRI which eliminates any other cause such as tumor, abscess, vascular disease … and also sometimes confirms the diagnosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is usually done to check for other disorders that could be responsible for the symptoms. In people with advanced progressive supranuclear palsy, MRI scans show that the upper part of the brainstem (midbrain) has shrunk and is smaller than normal.

The oculomotor examination which records the movement of the eyes and provides additional support for the diagnosis.

People with progressive supranuclear palsy have difficulty moving their eyes intentionally, especially up or down, but also end up having difficulty moving them to the side. . However, when a doctor asks them to look at an object straight ahead and then turn their head in one direction, the eyes move normally and involuntarily in the opposite direction to allow them to look at the object. This test can detect loss of voluntary eye movements, but the retention of involuntary eye movements characteristic of progressive supranuclear palsy and confirm the diagnosis.

What signs should you be worried?

PSP is a neurodegenerative disease, that is, it causes degeneration in the functioning of nerve cells. It is also accompanied by abnormal deposits of the Tau protein in the basal ganglia of the brain and brainstem.

There are 5 main forms of PSP, so the first signs of the disease can be very variable. The following main symptoms can nevertheless be established:

– progressive balance disorders, with more and more frequent falls (falls backwards, for example);

– visual difficulties, with slow and limited eye movements (impression of staring), impression of blurred vision, dry eyes and sensitive to light (sometimes requiring the wearing of sunglasses);

– changes in behavior: slowing down, loss of interest, impulsiveness, aggressiveness, instability of attention …

difficulties in speaking: finding words, articulating.

– PSP can begin with different symptoms defining several forms of the disease. However, as these evolve, almost all people will present with a significant difficulty in walking with frequent falls, disturbances in eye movement, speech, swallowing and intellectual disturbances.

Is it hereditary?

No. But there are a few exceptional forms where heredity is responsible for the disease.

Causes

The causes were unknown to Steele, Richardson, and Olszewski in 1964. Even today little is known about the causes of PSP. Three genetic defects are known, one in the gene coding for the tau protein, which can trigger PSP.

This may occurs when brain cells in certain parts of the brain are damaged as a result of a build-up of a protein called tau.

PSP is a tauopathy, a disease in which the protein tau clumps instead of stabilizing the cell structure. Affected nerve cells die. Diseased cells are repaired or broken down. The protein PERK (Protein Kinase RNA-like Endoplasmic Reticulum Kinase) as part of this maintenance system is defective in PSP. It reacts – with the protein kinase Ire1 (inositol-requiring enzyme 1) and the transcription factor ATF6 (Activating Transcription Factor 6) – to a protein misfolding in the form of an Unfolded Protein Response.

PSP symptoms decrease when PERK is activated with pharmaceuticals, i.e. the effect of PERK is increased. PERK helps eliminate faulty tau molecules. These also occur in other brain diseases.

As far as the other cases are concerned, it is assumed that a toxic substance (neurotoxin) can sometimes trigger PSP with a genetic predisposition, as PSP-like diseases occurred more frequently on the islands of Guam (here Lytico-Bodig) and Guadeloupe. It is suspected that substances occurring on both islands are the cause of the disease. Alternative hypotheses is from an infection with previously unknown viruses.

Is there a treatment?

Currently, no medication or treatment can cure this disease.

Sometimes medicines used to treat Parkinson’s disease.

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy.

Progressive supranuclear palsy is incurable.

Sometimes the medicines used to treat Parkinson’s disease (such as levodopa and amantadine) temporarily relieve stiffness.

Physiotherapists and occupational therapists can suggest exercises that will help keep joints flexible and help people function better. They can also recommend safe strategies and measures to reduce the risk of falling.

Since progressive supranuclear palsy is fatal, people with this condition should prepare advance directives indicating the type of medical care they wish to receive at the end of life.

Prognosis

The disease is not directly fatal, on the other hand it shortens the life expectancy of those who have it. Given the diagnostic error on the one hand and the patient’s age and general state of health on the other hand, this life expectancy for a patient diagnosed with PSP rarely exceeds 15 years. On the other hand, the averages in this area are not significant because they do not reflect the strong disparities from one patient to another. The most accepted average is around 7 years. The main causes of reduced life expectancy, or even mortality, in PSP patients can be:

- accidental falls backwards, this is the characteristic of the disease;

- respiratory tract infections due to repeated aspiration;

- general and premature exhaustion of the patient, especially if the patient suffers from other pathologies and is elderly.

Five types of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy and diagnostic difficulties

When looking at the brains of those with a pathological diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), there are some differences:

(a) in the severity of pathology in the brain,

(b) in the distribution of pathology in the brain, and

(c) clinical features

Presumably three of the disease “subgroups” the authors refer to include: Richardson’s Syndrome (described elsewhere as “classic PSP”), PSP-Parkinsonism, and primary progressive freezing gait (PPFG). I’m unclear if “pure akinesia with gait freezing” (PAGF) is another PSP subgroup or not. (Or if it’s the new name for PPFG. So many acronyms!)

This review article addresses these differences. You’ll have to check out the full article to see all the differences. In this post, I’m only sharing the differences in “clinical features” or symptoms.

The authors describe five clinical subgroups or types of PSP:

1- Richardson’s syndrome (“classic PSP”)

Symptoms may include: lurching gait; postural instability; unexplained backwards falls; personality change; cognitive decline; slowing of vertical saccadic eye movements (“an early telltale sign”); eyelid abnormalities; severely impaired spontaneous blink rate; slow, slurred, growling speech; swallowing difficulties; overactivity of the frontalis; surprised, worried facial appearance; muscle tone can be normal; acoustic startle response absent in most patients; auditory blink reflex absent in most patients.

“The median survival in the original series was 5 years from disease onset; in larger, more recent studies, disease durations to death of 5 to 8 years have been reported.”

2- PSP-Parkinsonism (PSP-P)

Symptoms may include: limb bradykinesia; limb rigidity is more common and severe than in patients with Richardson’s syndrome; jerky postural tremor; 4-6 Hz rest tremor; asymmetry of limb signs in some cases; axial rigidity; “moderate or good improvement in bradykinesia and rigidity” following levodopa therapy, “although the response is rarely excellent”; acoustic startle response absent in most patients; auditory blink reflex preserved in all patients.

Those with PSP-P are “commonly misdiagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.”

“Falls and cognitive dysfunction occur later in PSP-P than they do in Richardson’s syndrome and, perhaps as a consequence, the time for disease duration to death is about 3 years longer in PSP-P.”

PSP-P compared to other disorders:

(a) “PSP-P and Richardson’s syndrome can be distinguished by their different clinical pictures in the first 2 years; however, there is clinical overlap, and after 6 years of follow up the clinical phenomenology might become similar.”

(b) auditory blink reflex “was absent in most patients with Richardson’s syndrome but was preserved in all patients with PSP-P”

(c) “[We] emphasize the difficulty in separating these [PSP-P] patients from those with [PD]. Early pointers that might help a clinical diagnosis of PSP-P could include rapid progression, prominent axial symptomatology, or a poor response to levodopa…”

“In a few patients, a purely parkinsonian syndrome predominates until death, and abnormalities of eye movement or other characteristics of Richardson’s syndrome might never appear. A sustained response to levodopa and drug-induced choreic dyskinesias with a long duration of disease seem to characterise these patients.”

The prevalence of the PSP-P type seems to be between 8% and 32% of those with PSP pathology.

3 – PSP-Pure akinesia with gait freezing (PSP-PAGF)

Symptoms may include: “progressive onset of gait disturbance with start hesitation and subsequent freezing of gait, speech, or writing”; “without rigidity, tremor, dementia, or eye movement abnormality during the first 5 years of the disease”; no benefit to levodopa therapy; acoustic startle response present in all patients; auditory blink reflex preserved in all patients.

PAGF was “first described in 1974 in two patients who developed freezing of gait, writing, and speech, with paradoxical kinesia. At presentation, these patients were cognitively intact, had no abnormalities of eye movement, and, as is the case in many patients, there was a long disease duration without the development of other parkinsonian features.”

“The median duration of disease was 11 years.”

Fewer than 1% have this type of PSP.

4- PSP-Corticobasal syndrome (PSP-CBS)

Symptoms may include: asymmetric limb dystonia; apraxia; alien limb. “An increase in latency to initiate saccadic eye movements, which leads eventually to compensatory head tilts, is the most common eye movement abnormality and is typically more pronounced on the side on which the apraxia predominates. The distinction between this and the typical slowness of saccadic eye movements in Richardson’s syndrome can be difficult to make early in the course of the disease.”

“Most patients with PSP-CBS eventually develop postural instability but this occurs much later in Richardson’s syndrome.”

“Pathological series have indicated that only 50% of patients with CBS have pathology that is typical of corticobasal degeneration… Cerebrovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and progressive supranuclear pathology account for most of the other patients.”

“PSP-CBS seems to be a rare presentation of PSP-tau pathology; only five patients from a pathological series of 160 patients with PSP was identified with asymmetric limb dystonia, apraxia, and alien limb phenomena.”

5- Progressive non-fluent aphasia (PNFA)

Symptoms may include: non-fluent spontaneous speech, with hesitancy; agrammatism; “phonemic errors that require substantial effort in speech production.”

“In a small case series, five of seven patients who presented with PNFA and prominent early apraxia of speech had underlying PSP-tau pathology. The other two patients had Pick’s disease and corticobasal degeneration… The apparent specificity of prominent early apraxia of speech for tauopathies, particularly PSP-tau pathology, has [led] to the suggestion that this syndrome should be regarded as a clinical subtype of PSP. Patients who present with prominent early apraxia of speech do so at similar ages of onset or disease duration as patients with Richardson’s syndrome.”

Conclusions. In the conclusion to the review article, the authors state:

“The early recognition of patients with Richardson’s syndrome, PSP-P, PSP-CBS, PAGF, or PSP-PNFA would be enhanced by biomarkers for tauopathies and clinical criteria with a high positive predictive value for Parkinson’s disease, which is the main differential diagnosis for these conditions and is 30 times more prevalent than PSP.”

Information: Cleverly Smart is not a substitute for a doctor. Always consult a doctor to treat your health condition.

Sources: PinterPandai, NHS (UK), NIH National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke, The Johns Hopkins University

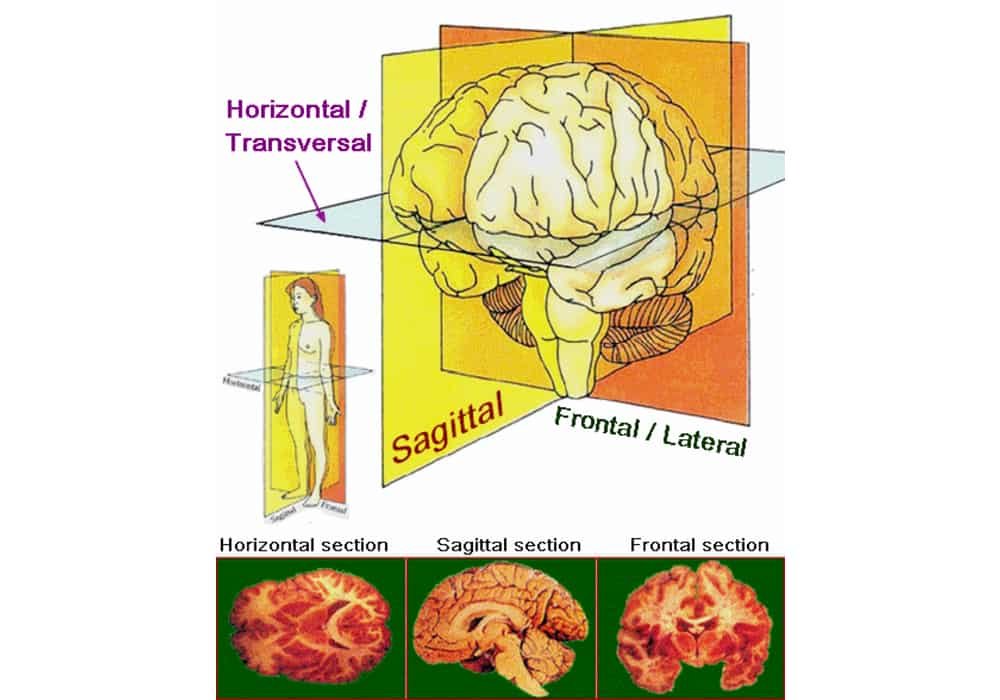

Photo credit: Zwarck / Wikimedia Commons

Photo explanation: Main anatomical planes and axes applied to sections of the brain.