What is Uterine Cancer (Endometrial Cancer)?

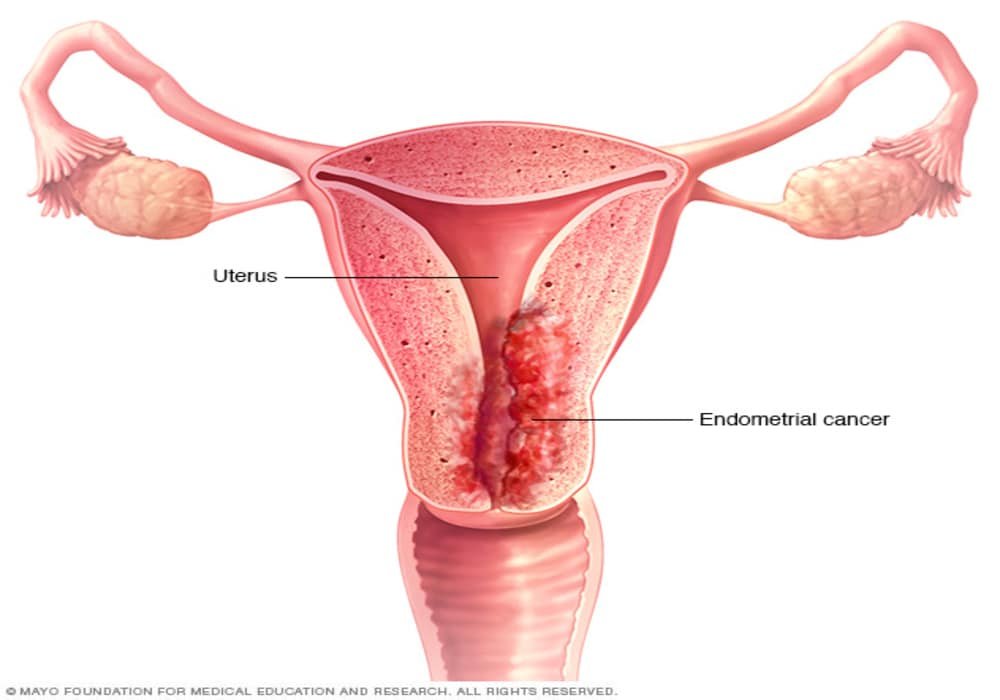

Uterine cancer, also known as womb cancer or endometrial cancer, is the most common type of cancer in the female reproductive system. It begins as a malignant tumor in the cells of the uterus, capable of invading surrounding tissues and spreading (metastasizing) to other parts of the body. It is the fourth most common cancer in women in developed countries.

The uterus, or womb, is a hollow, pear-shaped organ where a fetus grows during pregnancy. The lining of the uterus, called the endometrium, is made up of gland-rich tissue. Abnormal changes in the cells of the uterus can lead to non-cancerous conditions like endometriosis or uterine fibroids. They can also cause precancerous conditions, such as atypical endometrial hyperplasia, which may progress to cancer if untreated.

Most uterine cancers are endometrial carcinomas, starting in the lining of the uterus. Another type, uterine sarcoma, develops in the supportive tissues of the uterus, such as muscles or fibrous tissues. Rare cancers like carcinosarcoma and gestational trophoblastic disease can also affect the uterus.

The uterus plays a crucial role in reproduction. Every month, the uterine lining thickens in preparation for pregnancy. If pregnancy doesn’t occur, the lining is shed during menstruation, a cycle that continues until menopause.

Types of Uterine (Womb) Cancer

The two most common types are endometrioid adenocarcinoma and uterine serous carcinoma. However, there are other rarer types of uterine cancer as well.

Below are the main types:

- Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma: This is the most common type of uterine cancer, accounting for about 80% of cases. It develops from the cells lining the inner wall of the uterus (endometrium). It is often associated with excess estrogen and is more common in women who are obese or have diabetes.

- Uterine Serous Carcinoma (USC): This is a more aggressive type of uterine cancer, accounting for about 10% of cases. It tends to have a poorer prognosis and is more likely to spread beyond the uterus. USC is less hormone-dependent than endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

- Clear Cell Carcinoma: This is a rare type of uterine cancer, accounting for about 5% of cases. It is characterized by cells with clear cytoplasm when viewed under a microscope. Clear cell carcinoma is associated with a worse prognosis.

- Carcinosarcoma (Mixed Mesodermal Tumor): Carcinosarcoma is a rare and aggressive type of uterine cancer that contains both carcinomatous (carcinoma) and sarcomatous (sarcoma) components. It is also known as malignant mixed Müllerian tumor.

- Adenosquamous Carcinoma: This type of uterine cancer contains both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma components. It is less common than the other types.

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Squamous cell carcinoma of the uterus is a rare subtype that develops from the squamous cells of the cervix. It is distinct from the more common type, endometrial cancer.

It’s essential to note that the treatment and prognosis for each type of uterine cancer may vary. Early detection, accurate diagnosis, and appropriate treatment are crucial for improving the chances of successful outcomes. Treatment plans are typically personalized based on the stage, type, and individual health status of the patient. Regular gynecological check-ups and awareness of potential symptoms can aid in early diagnosis and timely intervention.

Symptoms of uterine cancer

Cancer of the uterus can cause various signs and symptoms as the cancer grows. Other medical conditions can cause the same symptoms as uterine cancer.

The most common symptom of uterine cancer is abnormal vaginal bleeding. This includes changes in your periods (heavier, longer, or more frequent periods than normal), bleeding between periods, bleeding after menopause, and light vaginal bleeding.

First signs of womb cancer (uterine or endometrial cancer)

The first signs of womb cancer (uterine or endometrial cancer) often appear as changes in vaginal bleeding patterns. The most common early symptoms include:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding: this can manifest as heavier or longer periods, bleeding between periods, or post-menopausal bleeding (bleeding after menopause is a key warning sign).

- Unusual vaginal discharge: this may be watery, pink, or bloody and can occur even when you’re not menstruating.

- Pelvic pain: some women experience pain or pressure in the pelvis or lower abdomen.

- Pain during intercourse.

- Pain during urination or other urinary difficulties.

If you notice these symptoms, it’s crucial to seek medical attention for a proper diagnosis. These signs can also indicate other health conditions, so it’s important to have a healthcare professional assess them.

For more detailed information, you can visit sources like the American Cancer Society (Cancer Info) and Cancer Research UK (Cancer Info).

Other signs and symptoms of uterine cancer include:

- unusual vaginal discharge, which may be foul-smelling, look like pus, or be tinged with blood

pain during sex. - pain or pressure in the pelvis, lower abdomen, back, or legs.

- pain during urination, difficulty passing urine, or blood in the urine.

- pain during bowel movements, difficulty in defecating, or blood in the stool.

- bleeding from the bladder or rectum.

- accumulation of fluid in the abdomen (called ascites) or legs (called lymphedema).

- weightloss.

- loss of appetite.

- difficulty in breathing.

Risk factors for uterine cancer

A risk factor is something, like a behavior, substance, or condition that increases your risk for developing cancer. Most cancers are caused by many risk factors, but uterine cancer can develop in women who do not have any of the risk factors described below.

Atypical endometrial hyperplasia is a precancerous condition of the uterus. It’s not cancer, but it can turn into cancer of the uterus if left untreated. Some of the risk factors for uterine cancer can also cause atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Risk factors are usually ranked from most important to least important. But in most cases, it is impossible to rank them with absolute certainty.

Risk factors

- Estrogen hormone replacement therapy

- Number of periods

- No childbirth

- Overweight and obesity

- Tamoxifen

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- Diabetes

- Radiotherapy to the pelvis

- Estrogen-secreting tumors of the ovary

- Little physical activity

- Lynch Syndrome

- Cowden Syndrome

There is convincing evidence that the following factors increase your risk of uterine cancer.

Estrogen hormone replacement therapy

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) uses female sex hormones (estrogen, progesterone, or both) to control symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and mood swings. Research shows that taking estrogen-only HRT (no progesterone) increases the risk of uterine cancer. Combining estrogen with progesterone (combined HRT) does not increase the risk of uterine cancer.

Number of periods

Women who have a greater number of periods in their lifetime are at greater risk of developing uterine cancer. We are talking about women who started menstruating before the age of 12 (early menstruation, or early menarche) or whose periods stopped after 55 (late menopause). Early periods like late menopause mean that the body makes estrogen longer, which increases the risk of uterine cancer.

No childbirth

Women who never give birth to a child are twice as likely to develop uterine cancer than women who give birth at least once. During pregnancy, the level of estrogen in the body drops. The more a woman gives birth, the less estrogen her body makes and the lower her risk of developing uterine cancer.

Overweight and obesity

A woman who is overweight or obese has a higher risk of developing uterine cancer. A woman who has a lot of body fat may be up to 10 times more likely to have it.

Researchers are not sure why being overweight and obese increases the risk of uterine cancer. This may be because having too much fatty tissue increases the level of estrogen in the body, and too much estrogen increases the risk of uterine cancer. In obese people, the blood levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 are often high, which can help some tumors to grow. The risk of developing uterine cancer is even higher in women who are overweight or obese and have high blood pressure or diabetes.

Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen (Nolvadex, Tamofen) is a hormonal medicine given to treat certain cancers, most often breast cancer. Women who take tamoxifen for 2 years or more have a higher risk of developing uterine cancer.

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is caused by changes in the normal hormonal cycle and the normal ovulation process. Many women with polycystic ovary syndrome don’t get their period often, or don’t at all, and may have difficulty getting pregnant. These women are also at higher risk of developing uterine cancer.

Diabetes

Diabetes, also called diabetes mellitus, is a chronic disease that increases the rate of blood sugar. Women with diabetes are about twice as likely to get uterine cancer as women who don’t have diabetes. Women with diabetes who are also obese or have high blood pressure are at an even greater risk of developing uterine cancer.

Radiotherapy to the pelvis

Radiation therapy is used to treat certain cancers or uterine bleeding caused by a non-cancerous (benign) condition. Women who receive large doses of radiation therapy to the pelvis are at greater risk of developing uterine cancer.

Estrogen-secreting tumors of the ovary

A woman with an ovarian tumor that makes estrogen is more likely to get cancer of the uterus because her estrogen levels are high.

Little physical activity

Women who do little physical activity are more likely to get cancer of the uterus. Being active seems to protect against uterine cancer.

Lynch Syndrome

Lynch syndrome (also called hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer or HNPCC) is an inherited disease caused by a change (mutation) that has occurred in one of DNA’s mismatched repair genes. These genes usually correct mistakes made when copying DNA during cell division. In the case of Lynch syndrome, the mismatched repair genes do not work properly and the cells that carry the errors are not repaired. These abnormal cells eventually build up and can become cancerous.

Women with Lynch syndrome have a higher risk of developing uterine cancer during their lifetime. These women tend to get cancer of the uterus at a younger age than women in general.

Cowden Syndrome

Cowden syndrome is an inherited disease that can cause many non-cancerous masses called hamartomas to form in the skin, breast, thyroid gland, colon, small intestine and mouth. The Cowden syndrome is caused by a mutation in the PTEN gene. It increases the risk of uterine cancer.

Possible risk factors

The following factors have been linked to uterine cancer, but there is insufficient evidence to suggest that they are risk factors. More research is needed to clarify the role of these factors in the development of uterine cancer:

- physical inactivity (sedentary habits)

- family history of uterine cancer

- high blood pressure (hypertension)

- exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES), a form of estrogen made in the laboratory

- high glycemic load (the glycemic load is a measure of how quickly certain amounts of food raise blood sugar levels)

No link to uterine cancer

Important research indicates that there is no link between intrauterine devices (a type of birth control) and the increased risk of uterine cancer.

How to Reduce the Risk of Uterine Cancer?

Lower your risk of uterine cancer by following these steps:

- Maintain a healthy weight: Eating well and staying physically active can lower your risk.

- Move more, sit less: Regular physical activity reduces cancer risk.

- Consider protective factors: Birth control pills with estrogen and progesterone help reduce the risk. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) may benefit from these pills to regulate hormones.

- Have children: Pregnancy lowers estrogen exposure, reducing cancer risk.

- Drink coffee: Studies suggest it may lower your uterine cancer risk, whether caffeinated or not.

Identifying High Risk

If you have a higher risk (e.g., atypical endometrial hyperplasia or Lynch syndrome), consult your doctor for regular check-ups and possible preventive options like a prophylactic hysterectomy.

Early Detection of Uterine Cancer

Early detection improves treatment outcomes. Regular gynecological exams and Pap tests can help detect cancer early, but additional tests like a pelvic exam, transvaginal ultrasound, hysteroscopy, or endometrial biopsy may be needed to catch uterine cancer in its early stages.

Diagnosis of uterine cancer

The diagnostic process for uterine cancer usually begins with a visit to your family doctor. Your doctor will ask you about your symptoms and do a physical exam. Based on this information, your doctor may refer you to a specialist or order tests to check for uterine cancer or other health problems.

The diagnostic process can seem long and overwhelming. It’s okay to worry, but try to remember that other medical conditions can cause uterine cancer-like symptoms. It is important that the healthcare team rule out any other possible cause of the condition before making a diagnosis of uterine cancer.

The following tests are commonly used to rule out or confirm a diagnosis of uterine cancer. Many tests that can diagnose cancer are also used to determine the stage, that is, the extent of progression of the disease. Your doctor may also order other tests to assess your general health and to help plan your treatment.

Medical history and physical examination

A medical history is a history of symptoms, risk factors, and any medical events and conditions a person has had in the past. When checking your medical history, your doctor will ask you questions about your personal history of:

- symptoms that may indicate the presence of uterine cancer

- use of hormone replacement therapy

- menstruation

- pregnancy

- use of tamoxifen (Nolvadex, Tamofen) to treat or prevent breast cancer

- endometrial hyperplasia

- polycystic ovary syndrome or ovarian tumors

- radiotherapy to the pelvis

- overweight or obese

- diabetes

- hypertension

Your doctor may also ask you about your family history of:

- cancer of the uterus, ovary, breast or colon

- other hereditary cancer syndromes

The physical exam allows the doctor to look for any signs of uterine cancer. During the physical examination, the doctor may:

- measure your weight and blood pressure

- auscultate your chest

- perform a pelvic exam and digital rectal exam

- feel your abdomen to check if your liver is swollen, there are lumps, or if there is a buildup of fluid (called ascites)

- feel the lymph nodes in the groin and those above the collarbone for swelling

Complete blood count (CBC)

The complete blood count (CBC) is used to assess the quantity and quality of white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets. It is used to check for anemia caused by vaginal bleeding. The CBC also allows doctors to obtain benchmarks against which to compare the results of future blood tests performed during and after treatment.

Transvaginal ultrasound

In an ultrasound, high-frequency sound waves are used to produce images of body structures. In transvaginal ultrasound, sound waves are produced by a small ultrasound probe that is gently inserted into the opening of the vagina.

Transvaginal ultrasound can be used for:

- determine the thickness of the endometrium

- check for lumps in the uterus

- check to see if cancer has invaded the muscular layer of the lining of the uterus (called the myometrium)

- check to see if the cancer has spread to other areas of the pelvis

Biopsy

During a biopsy, the doctor removes tissues or cells from the body for analysis by a pathology laboratory. The laboratory report confirms the presence or absence of cancer cells in the sample.

An endometrial biopsy is a procedure that removes small pieces of the lining of the uterus (called the endometrium). It is usually performed in the doctor’s office. Sometimes a hysteroscopy (a type of endoscopy) is done at the same time.

Dilation and curettage (DC) is a procedure in which the cervix (the lower, narrow part of the uterus) is widened, or dilated, so that a curette (a curette-shaped instrument) can be inserted into it. sharp-edged spoon) into the uterus for the purpose of removing endometrial cells, tissue or masses. It may be used if the sample taken from an endometrial biopsy was too small to make a diagnosis, if the results were inconclusive, or if endometrial hyperplasia was detected.

This procedure is performed in an operating room.

Endoscopy

Endoscopy allows the doctor to observe the inside of a body cavity using a rigid or flexible tube, at the end of which are attached a lumen and a lens. This instrument is called an endoscope.

A hysteroscopy is often done when there is abnormal vaginal bleeding. This helps doctors detect and diagnose abnormal changes in the uterus. Sometimes a biopsy is done during a hysteroscopy. The tissue samples taken are then examined to determine whether the changes are non-cancerous (benign), precancerous, or cancerous (malignant).

Sometimes a cystoscopy is done when the person has difficulty passing urine or notices blood in their urine. Doctors use it to find out if the cancer has spread to the bladder or urethra.

Sometimes a proctoscopy is done when bowel movements change. Doctors use it to find out if the cancer has spread to the rectum.

Blood biochemical analyzes

In blood chemistry tests, the level of certain chemicals in the blood is measured. They make it possible to evaluate the functioning of certain organs and to detect abnormalities. To determine the stage of uterine cancer, the following blood chemistry tests can be done.

Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels can be measured to check kidney function. Higher than normal levels could mean that the cancer has spread to the ureters or kidneys.

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase can be measured to check liver function. Higher than normal levels could mean that the cancer has spread to the liver.

Determination of tumor markers

Tumor markers are substances found in the blood, tissues and fluids taken from the body. An abnormal level of a tumor marker can mean that a woman has cancer of the uterus.

Tumor marker assay is usually done to assess response to cancer treatment. It can also be used to diagnose cancer of the uterus.

Tumor antigen 125 (CA 125) can be measured. A higher than normal rate could indicate the presence of advanced or metastatic uterine cancer.

Tumor Markers: What They Are and How They’re Used to Diagnose and Monitor Cancer

Barium enema

A barium enema is an imaging test that uses a contrast medium (barium sulfate) and X-rays to produce images of the colon. It can be used to find out if the cancer has spread to the rectum. A barium enema may be done if a woman experiences symptoms that suggest the cancer may have spread to the rectum.

Pulmonary radiography

In an x-ray, low doses of radiation are used to produce images of the body’s structures on film. It is used to find out if uterine cancer has spread to the lungs.

Computed tomography (CT)

A computed tomography (CT) scan uses special x-ray machines to produce 3-dimensional and cross-sectional images of the body’s organs, tissues, bones and blood vessels. A computer assembles the photos into detailed images.

CT is used to determine if the cancer has spread to other organs or if it has come back after treatment.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), powerful magnetic forces and radio waves are used to produce cross-sectional images of the body’s organs, tissues, bones and blood vessels. A computer assembles the photos into 3-dimensional images.

MRIs are used to find out how much cancer has invaded the muscle layer of the lining of the uterus (called the myometrium). It can also help doctors determine if the cancer has spread to other organs or if it has come back after treatment.

Treatments for Uterine Cancer (Womb Cancer)

Your treatment plan will be customized based on the stage, tumor type, grade, and your health. Below are the main types of treatments:

1. Surgery

- Total hysterectomy: Removal of the uterus and cervix, sometimes including nearby lymph nodes.

- Radical hysterectomy: Removes the uterus, cervix, surrounding tissues, and parts of the vagina.

- Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: Removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes, often done with a hysterectomy.

- Lymph node dissection: Removes lymph nodes to check if cancer has spread.

- Omentectomy: Removes the omentum to examine for cancer cells.

- Pelvic exenteration: Removes the uterus, ovaries, vagina, and sometimes bladder or rectum for recurrent cancer.

- Tumor debulking: Removes as much of the tumor as possible in advanced cancer.

2. Radiation Therapy

- External beam radiation therapy (EBRT): Uses high-energy rays to target and kill cancer cells from outside the body.

- Brachytherapy: A type of internal radiation therapy where radioactive material is placed inside the body near the tumor.

- Radiation therapy may be used to treat any stage of uterine cancer. Women often receive external beam radiation therapy or brachytherapy.

3. Chemotherapy

- Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells, usually recommended for advanced stages or high-risk uterine cancer. Common drugs include carboplatin and paclitaxel.

4. Hormone Therapy

- Used for cancers that are hormone-sensitive. Progestins (synthetic progesterone) and aromatase inhibitors help slow cancer growth by lowering hormone levels. Hormonal therapy may be given after surgery for some stages of uterine cancer. It may also be used as the main treatment for advanced or recurrent uterine cancer.

5. Targeted Therapy

- Drugs like trastuzumab or lenvatinib target specific molecules within cancer cells to stop their growth without affecting normal cells.

6. Immunotherapy

- Uses the body’s immune system to fight cancer. Pembrolizumab, a common immunotherapy drug, can be used in certain advanced cases or recurrent uterine cancer.

7. Clinical Trials

- Participating in clinical trials can provide access to new, emerging treatments that might not yet be widely available. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, find and treat cancer.

Follow-up care

Follow-up after treatment is an important part of cancer care. You will need to have regular follow-up visits, especially in the first few years after treatment has finished. These visits allow your healthcare team to monitor your progress, detect early recurrences and help with recovery from previous treatment.

Histological classification of uterine cancer (grade)

To determine the grade of uterine cancer, the pathologist examines a sample of tissue taken from the uterus under a microscope. The pathologist assigns a grade of 1 to 3 to cancer of the uterus. The lower this number, the lower the rank.

The grade describes how cancer cells look and behave compared to normal cells. The term differentiation is used to refer to how different cancer cells are.

Low-grade cancer cells are well differentiated. They almost look like normal cells. They tend to grow slowly and are less likely to spread.

High-grade cancer cells are poorly differentiated or undifferentiated. Their appearance is less normal, or more abnormal. They tend to grow faster and are more likely to spread than low-grade cancer cells.

Knowing the grade gives your healthcare team an idea of how quickly cancer can grow and how likely it is to spread. It helps him plan your treatment. The grade can also help the healthcare team make your prognosis and predict how the cancer might respond to treatment.

Endometrial carcinoma

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) has developed a histological classification system for endometrial carcinoma. This system is based on the percentage of cells in the tumor that grow into lamellae (these are called solid components in the tumor) rather than forming glands. It can also take into account how abnormal the cells look.

Endometrial carcinoma

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) developed a grading system for endometrial carcinoma. It is based on the percentage of cells in the tumour that grow in sheets (called solid tumour growth) rather than form glands. It may also take into account how abnormal the cells appear.

| FIGO grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5% or less of tumour tissue is solid tumour growth.The cancer cells are well-differentiated. |

| 2 | 6%–50% of tissue is solid tumour growth.The cancer cells are moderately differentiated. |

| 3 | More than 50% of tissue is solid tumour growth.The cancer cells are poorly differentiated. |

Uterine sarcoma

Uterine sarcoma is a soft tissue sarcoma that begins in the muscle or connective tissue cells of the uterus. There are several grading systems used for soft tissue sarcomas. The French Federation of Comprehensive Cancer Centers (FNCLCC) system is most commonly used. In this system, the grade is based on the following 3 factors.

- Differentiation: The cells are given a score of 1–3 based on how they look. A score of 1 means the cancer cells look very similar to normal cells. A score of 3 means the cells look very abnormal.

- Mitotic count: The cancer cells are given a score of 1–3 based on how they are dividing. A score of 1 means the pathologist saw only a few cells dividing. A score of 3 means many cells were dividing.

- Tumor necrosis: The tumour is given a score of 0–2 based on how much of it is made up of dying tissue. A score of 0 means very little tissue is dying. A score of 2 means there is a large amount of dying tissue.

The scores for each factor are added up to determine the grade of the cancer. A higher score means a higher grade.

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| GX | Grade cannot be assessed |

| G1 | Total score of 2 or 3 |

| G2 | Total score of 4 or 5 |

| G3 | Total score of 6 or higher |

Stages of uterine cancer (womb cancer)

Staging describes or classifies a cancer based on how much cancer there is in the body and where it is when first diagnosed. This is often called the extent of cancer. Information from tests is used to find out the size of the tumour, which parts of the organ have cancer, whether the cancer has spread from where it first started and where the cancer has spread. Your healthcare team uses the stage to plan treatment and estimate the outcome (your prognosis).

The most common staging system for uterine cancer is the FIGO system. The FIGO system is used to stage endometrial carcinoma, uterine carcinosarcoma and uterine sarcoma. For these types of uterine cancer, there are 4 stages. Often the stages 1 to 4 are written as the Roman numerals I, II, III and IV. Generally, the higher the stage number, the more the cancer has spread. Talk to your doctor if you have questions about staging.

When describing the stage, doctors may use the words local, regional or distant. Local means that the cancer is only in the uterus and has not spread to other parts of the body. Regional means close to the uterus or around it, including lymph nodes in the pelvis and lymph nodes around the aorta (a large artery that carries blood away from the heart). Distant means in a part of the body farther from the uterus.

Endometrial carcinoma and uterine carcinosarcoma

Doctors use the following FIGO stages for endometrial carcinoma and uterine carcinosarcoma. The FIGO system does not include stage 0 (carcinoma in situ).

Stage 1A

The tumour is only in the inner lining of the uterus (called the endometrium) or it has grown less than halfway through the muscle layer of the uterus wall (called the myometrium).

Stage 1B

The tumour has grown halfway or more than halfway into the myometrium.

Stage 2

The tumour has grown into the cervix.

Stage 3A

The tumour has grown into the outer surface of the uterus (called the uterine serosa) or the fallopian tubes, ovaries or their supporting ligaments.

Stage 3B

The tumour has grown into or spread to the vagina or tissues next to the cervix and uterus (called the parametria).

Stage 3C

The cancer has spread to lymph nodes in the pelvis (called pelvic lymph nodes) or to lymph nodes around the aorta (called para-aortic lymph nodes).

Stage 4A

The tumour has grown into the lining of the bladder or intestines.

Stage 4B

The cancer has spread to other parts of the body (called distant metastasis), such as to the lungs, liver or bone. This is also called metastatic cancer.

Uterine sarcoma

Doctors use the following FIGO stages for uterine leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma.

Stage 1A

The tumour is only in the uterus and is not larger than 5 cm.

Stage 1B

The tumour is only in the uterus and is larger than 5 cm.

Stage 2A

The tumour has grown into the fallopian tubes, ovaries or their ligaments.

Stage 2B

The tumour has grown into other tissues in the pelvis.

Stage 3A

The tumour has grown into 1 area of the abdomen.

Stage 3B

The tumour has grown into 2 or more areas of the abdomen.

Stage 3C

The cancer has spread to lymph nodes in the pelvis or to lymph nodes around the aorta.

Stage 4A

The tumour has grown into the bladder or rectum.

Stage 4B

The cancer has spread to other parts of the body (called distant metastasis), such as to the lungs, liver or bone. This is also called metastatic cancer.

Recurrent uterine cancer

Recurrent uterine cancer means that the cancer has come back after it has been treated. If it comes back in the same place that the cancer first started, it’s called local recurrence.

If it comes back in tissues or lymph nodes close to where it first started, it’s called regional recurrence. It can also recur in another part of the body. This is called distant metastasis or distant recurrence.

If uterine cancer spreads

Cancer cells can spread from the uterus to other parts of the body. This spread is called metastasis.

Understanding how a type of cancer usually grows and spreads helps your healthcare team plan your treatment and future care. If uterine cancer spreads, it can spread to the following:

- middle layer of the wall of the uterus (called the myometrium)

- outer layer of the uterus (called the perimetrium)

- cervix (cervical)

- tissues around the uterus

- vagina

- fallopian tubes

- ovaries

- lymph nodes in the pelvis

- bladder

- rectum (anal)

- lymph nodes around the aorta (called para-arotic lymph nodes)

- lymph nodes above the collarbone

- abdominal cavity

- peritoneal cavity

- omentum (peritoneal folds that connect the stomach and duodenum with other abdominal organs)

- bones

- brain

- liver

- lungs

Prognosis and survival for uterine cancer

If you have uterine cancer, you may have questions about your prognosis. A prognosis is the doctor’s best estimate of how cancer will affect someone and how it will respond to treatment. Prognosis and survival depend on many factors. Only a doctor familiar with your medical history, the type, stage and characteristics of your cancer, the treatments chosen and the response to treatment can put all of this information together with survival statistics to arrive at a prognosis.

A prognostic factor is an aspect of the cancer or a characteristic of the person that the doctor will consider when making a prognosis. A predictive factor influences how a cancer will respond to a certain treatment. Prognostic and predictive factors are often discussed together. They both play a part in deciding on a treatment plan and a prognosis.

The following are prognostic and predictive factors for uterine cancer:

Grade

The grade is one of the more important prognostic factors. Grade 1 or 2 tumours have a better prognosis and are less likely to recur than Grade 3 tumours.

Myometrial invasion

Myometrial invasion is how far the tumour has grown into, or invaded, the middle layer of the uterus wall (called the myometrium). Doctors can use the degree of myometrial invasion to predict if the cancer will come back, or recur, and to predict survival. The deeper the tumour has grown into the myometrium, the poorer the prognosis.

Doctors often classify the degree of myometrial invasion as:

- none – the tumour hasn’t grown into the myometrium

- superficial – the tumour has grown less than halfway through the myometrium

- deep – the tumour has grown more than halfway through the myometrium

Myometrial invasion is closely linked to the grade of the tumour. A higher grade tumour has a greater chance of growing into the myometrium.

Stage

Stage 1 cancers have the most favourable prognosis. Cancers have a less favourable prognosis if they have spread outside of the uterus, including to the following:

- lymph nodes

- cervix

- structures in the pelvis and abdomen (also known as extra-uterine disease)

Type of tumour

Endometrial carcinomas have a more favourable prognosis than uterine sarcomas. Some types of tumours within these groups have more favourable prognoses than others. For example, endometrioid carcinomas have a more favourable prognosis than serous adenocarcinomas. Also, endometrial stromal sarcomas have a more favourable prognosis than uterine leiomyosarcomas.

Cancer cells in the peritoneal fluid

When cancer cells are in the fluid in the abdominal cavity (called peritoneal fluid), it often means that the cancer has spread outside the uterus. This prognostic factor is often linked with other factors, such as how deep the tumour has grown into the myometrium and if the cancer has spread to lymph nodes. Cancer cells in the peritoneal fluid (called positive peritoneal cytology) often means the cancer is more aggressive and it has a less favourable prognosis.

Hormone receptors

The presence of progesterone receptors on the cancer cells may be linked with a less aggressive cancer. Cancer cells that have progesterone receptors have a better response to hormonal therapy and a more favourable prognosis.

Age

Younger women tend to have a better prognosis than post-menopausal women. This is true even though younger women may not be diagnosed with uterine cancer based on their symptoms as quickly as older women. Younger women often have lower grade tumours that are found at an earlier stage and haven’t grown very deep into the myometrium. Older women often have a more aggressive type of tumour and more advanced disease. As a result, older women tend to have a less favourable prognosis.

Obesity

Obesity, especially when the woman also has diabetes and high blood pressure, has been linked with a less favourable prognosis.

Follow-up after treatment for uterine cancer

Follow-up care is a crucial part of cancer treatment, often involving specialists like a gynecologist, oncologist, and your family doctor. Your healthcare team will customize a follow-up plan to meet your specific needs.

Don’t wait until your next scheduled appointment to report any new symptoms and symptoms that don’t go away. Tell your healthcare team if you have:

- pain in the lower abdomen, pelvis, back or legs

- vaginal bleeding or discharge

- change in bladder habits

- change in bowel habits

- weight loss

- chronic cough

The chance of uterine cancer coming back, or recurring, is greatest within the first few years after treatment, so close follow-up is needed during this time.

Schedule for follow-up visits

Follow-up visits for uterine cancer are usually scheduled:

- every 3–4 months for the first 2–3 years after initial treatment

- every 6 months for the next 2–3 years

- yearly from then on

During follow-up visits

During a follow-up visit, your healthcare team will usually ask questions about the side effects of treatment and how you’re coping. Your doctor may do a physical exam, including:

- doing a pelvic exam

- feeling the lymph nodes in the neck and groin area

Tests are often part of follow-up care. You may have:

- a chest x-ray if you have a chronic cough

- a CT scan if you have symptoms or your doctor finds something during the physical exam

- blood tests to check cancer antigen 125 (CA125) levels if they were higher than normal before surgery for advanced stage cancer

If a recurrence is found, your healthcare team will assess you to determine the best treatment options.

Supportive care for uterine cancer

Supportive care helps women meet the physical, practical, emotional and spiritual challenges of uterine cancer. It is an important part of cancer care. There are many programs and services available to help meet the needs and improve the quality of life of people living with cancer and their loved ones, especially after treatment has ended.

Recovering from uterine cancer and adjusting to life after treatment is different for each person, depending on the extent of the disease, the type of treatment and many other factors. The end of cancer treatment may bring mixed emotions. Even though treatment has ended, there may be other issues to deal with, such as coping with long-term side effects. A woman who has been treated for uterine cancer may have concerns about the following.

Self-esteem and body image

How a person feels about or sees themselves is called self-esteem. Body image is a person’s perception of their own body. Uterine cancer and its treatments can affect a woman’s self-esteem and body image. Often this is because cancer or cancer treatments may result in body changes, such as:

- scars

- hair loss

- skin problems

- changes in body weight

- sexual problems

- an ostomy

- urinary or bowel problems

Some of these changes can be temporary, others will last for a long time and some will be permanent. For many women, body image and their perception of how others see them are closely linked to self-esteem. Loss of self-esteem may be a real concern for them and can cause considerable distress. Even though the effects of treatment may not always be visible to other people, body changes can still be troubling. Some women may be afraid to go out or that others will reject them. They may feel angry or upset.

A woman may feel differently about her body and herself as a woman, especially after a hysterectomy or pelvic exenteration. She may feel less like a woman or less feminine because she no longer has a uterus or has had vaginal reconstruction. A woman may also feel self-conscious because the way she urinates or has a bowel movement is different after a pelvic exenteration.

Sexuality

Some cancer treatments can cause sexual problems for women that make sex painful or difficult. For example, radiation therapy to the pelvis can cause vaginal dryness. Scarring after radiation therapy to the pelvic area or some surgeries for uterine cancer can also cause vaginal narrowing (also called vaginal stenosis). Some treatments can cause women to enter menopause early (called treatment-induced menopause).

Some women may have other sexuality problems, such as a loss of interest in sex. It is common to have a lower sex drive around the time of diagnosis and treatment.

There are ways to manage most sexual problems that develop because of treatments for uterine cancer. When a woman first starts having sex after treatment, she may be afraid that it will be painful or that she will not have an orgasm. It may take time for partners to feel comfortable with each other again, and the first attempts at being intimate with a partner may be disappointing. Some women and their partners may need counselling to help them cope with these feelings and the effects of cancer treatments on their ability to have sex.

Fertility problems

Fertility problems can occur after treatment with radiation therapy or chemotherapy for uterine cancer. Women who have had a hysterectomy will not be able to become pregnant.

Before you start any treatment for uterine cancer, talk to your healthcare team about possible side effects that may affect your ability to have children after treatment. You can work with your healthcare team to discuss and plan fertility options before cancer treatment begins.

Lymphedema

Lymphedema is a chronic form of swelling that occurs when lymph fluid builds up in soft tissues. It usually occurs in parts of the body where large numbers of lymph nodes have been removed.

You may have lymphedema in your legs if lymph nodes were removed from your pelvis during surgery to treat uterine cancer. Lymphedema is more likely to occur if you were also given radiation therapy to the pelvis.

If lymphedema develops, your healthcare team can suggest ways to help prevent further fluid buildup and reduce swelling as much as possible. This may include elevating the limb, exercise, physical therapy and pain management. You can also ask for a referral to a healthcare professional who specializes in managing lymphedema.

Recurrence

Many women who are treated for uterine cancer worry that the cancer will come back, or recur. It is important to learn how to deal with these fears to maintain a good quality of life.

In addition to the support offered by the treatment team, a mental health professional, such as a social worker or counsellor, can help you learn how to cope and live with a diagnosis of uterine cancer.

Second cancers

Although uncommon, a different (second) cancer may develop after treatment for uterine cancer. While the possibility of developing a second cancer is frightening, the benefit of treating uterine cancer with chemotherapy or radiation therapy usually far outweighs the risk of developing another cancer. Whether or not a second cancer develops depends on the type and dose of chemotherapy drugs given and if radiation therapy was also given. The combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy increases the risk of second cancers.

Women who have radiation therapy to the pelvis have a small risk of developing a second cancer in the area treated with radiation. This area can include the colon, rectum, anus or bladder.

Women who have chemotherapy for uterine cancer can develop a second cancer at any time, but it usually occurs up to 10 years after treatment. The most common cancer that develops in women treated with chemotherapy for uterine cancer is acute myelogenous leukemia (AML).

Living a healthy lifestyle and working with your healthcare professional to develop a wellness plan for staying healthy may help lower the risk of second cancers. Routine screening to find a second cancer early, being aware of changes in your health and reporting problems to your doctor are also important parts of follow-up care after cancer treatment.

Ostomy care

An ostomy connects an internal cavity to an opening (stoma) on the abdomen. Women who have a pelvic exenteration will have the bladder, rectum or both removed. A urostomy allows urine to pass out of the body and a colostomy allows stool to pass out of the body. Women who have the bladder and rectum removed will have 2 ostomies.

Many women can adapt to and live normally with an ostomy, although they have to learn new skills and how to care for it. Specially trained healthcare professionals (called enterostomal therapists) teach people how to care for their ostomies.

Conclusion

Uterine (womb) cancer is a serious condition, but with early detection and appropriate treatment, the chances of a successful outcome are significantly higher. Being aware of the symptoms, knowing your risk factors, and taking preventive measures like maintaining a healthy lifestyle are essential steps. Regular gynecological check-ups and timely medical attention can help detect any abnormalities early, making a crucial difference in treatment success.

List of all Cancers

The word “cancer” is a generic term for a large group of diseases that can affect any part of the body. We also speak of malignant tumors or neoplasms. One of the hallmarks of cancer is the rapid multiplication of abnormal growing cells, which can invade nearby parts of the body and then migrate to other organs. This is called metastasis, which is the main cause of death from cancer. Types of cancer (in alphabetical order of the area concerned):

Information: Cleverly Smart is not a substitute for a doctor. Always consult a doctor to treat your health condition.

Sources: PinterPandai, American Cancer Society, Web MD, Cancer Center, Cleveland Clinic

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons